US fiscal and monetary expansions undeterred: playing with fire?

The US, and the world, suffered a pandemic shock in 2020 which required extreme measures to avoid falling into a self-sustaining economic depression. In historical terms, the expansion of federal expenditures and monetary aggregates in the US surpassed anything we might have seen in the past. The pandemic induced contraction was also uniquely abrupt. The 2020 response has been proven right. It is the 2021 continuation of that trend that will probably be proven wrong and unnecessary, as evidence of resuming activity accumulates for all to witness and vaccines are rapidly being distributed. There is no need to raise the specter of both inflation and dollar devaluation for no clear gains in the short term beyond what is already positively happening across the economy, even without further stimuli.

The following graphs should contribute to a better understanding of the main issues involved.

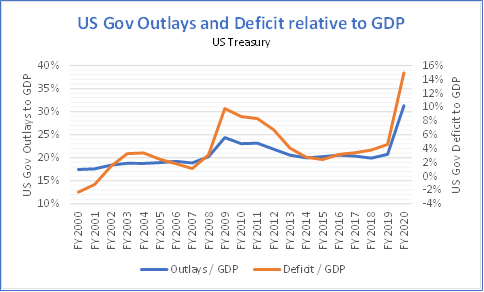

Government expenditures increased by 47%, to US$ 6.5 trillion in fiscal year 2020 – ended September 2020 -. Assuming a “correct” allocation of these resources, government expenditures temporarily reached 31% of GDP, compared with a two decade 20% average.

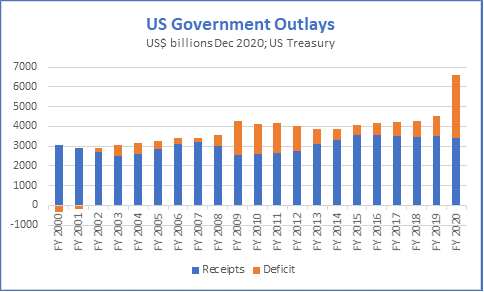

For the last decade, yearly government expenditures fluctuated around US$ 4.1 trillion – in December 2020 US$ – until 2019, when they ended up in US$ 4.5 trillion, while peaking a year later with US$ 2 trillion additional outlays at US$ 6.5 trillion. Receipts have been persistently stable, near US$ 3.5 trillion for the last five years, and amazingly resilient during 2020 with a relatively small 2.6% annual decrease – remember last tax reform disaster in the making? -.

In the midst of 2008-09 Great Recession, government expenditures increased by 28% with respect to year 2007, temporarily reaching almost 25% of GDP. That additional effort was almost half the present one when both expansions are compared with their respective previous federal outlays.

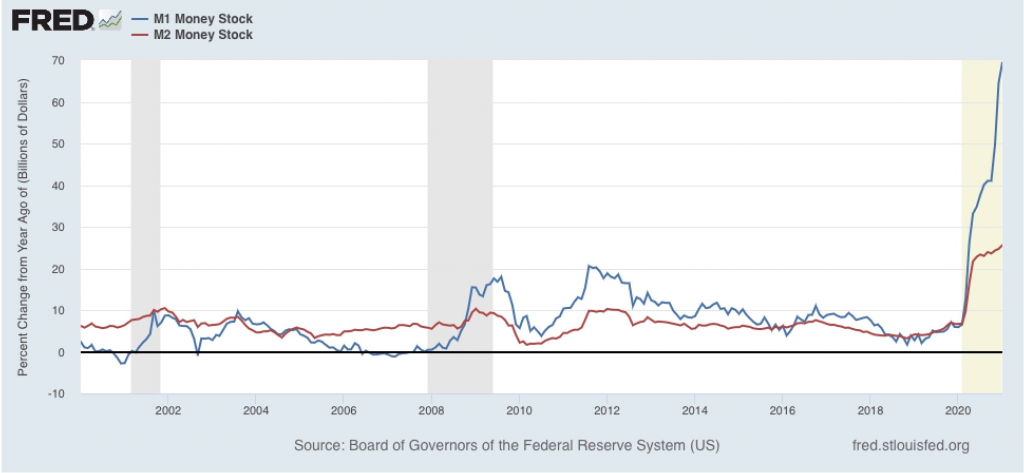

As for monetary policies, aggregates M1 and M2 ended up growing 66% and 25% in December 2020, respectively, compared to previous December 2019[1] levels. Again, an expansion in the pool of liquidity not ever witnessed in the past.

[1] Growth rates are estimated using Federal Reserve monetary aggregates definitions under the same basis – they were partially changed in May 2020, primarily on M1 series components -.

In 2008-09 these same monetary aggregates increased by 18% and 9%, respectively, with respect to previous year levels, to face the menacing liquidity crunch the financial system was entering into. New monetary growth rates in 2020 more than double those then pursued in the Great Recession, even considering more stable M2 aggregates.

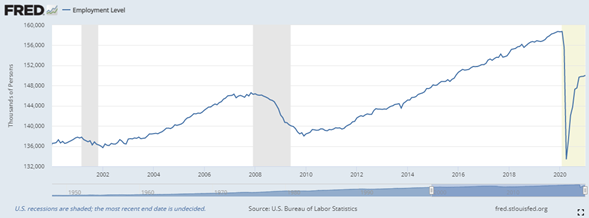

How about employment levels? It took seven years to get back to 146 million jobs that existed in the US in 2007, before the financial crisis. In pandemic times, out of 25 million job losses by mid-2020, 17 million have already been “recovered” in eight months.

Retail sales have been bigger than one year ago since July 2020, in nominal terms. US GDP is poised to regain its 2019 level during 2021. It took five years to regain 2007 US GDP in real terms.

Given this set up and the promising conditions under which US economy is now moving on, is it necessary to continue this pressing expansiveness in fiscal and monetary conditions? Would not be more prudent to start decelerating these growth rates while acknowledging visibly improving data on activity across the board? This is not a binary discussion, but one over degrees of excess efforts that should, in time, gradually evanesce.

As presently discussed, a US$ 1.9 trillion stimulus package that keeps government expenditures as if nothing had already improved seems far off normal boundaries, and more so when monetary conditions have relentlessly continued their expansionary trend. Let us not forget that back in December 2020 a US$ 900 billion stimulus package was also approved. Not all these resources are to be used in present fiscal year, but there is no way not to see the excesses involved. These fiscal expansions are not by themselves inflationary – they could just replace private expenditures -, but they indeed show a clear deterioration in US domestic policies. There was even an attempt to double federal minimum wages to US$ 15 per hour, equivalent to 60% of present median workers earnings, with “minor” employment consequences … So far, a failed attempt, but a very indicative one.

No surprise, then, when inflationary fears appear in the horizon and equity and bond prices react … The average expected inflation rate estimated by the difference between the 30 year nominal Treasury bond and inflation indexed equivalent bond yields has already gone up almost 100 basis points in less than a year towards 2.2% in annual terms. And there is no indication yet it will stop going up: on the contrary, there are good reasons not to do so.

And the US real exchange rate? Going down, slowly, but down: 9% since April 2020 peak, and even below its level existing before the pandemic struck the world.

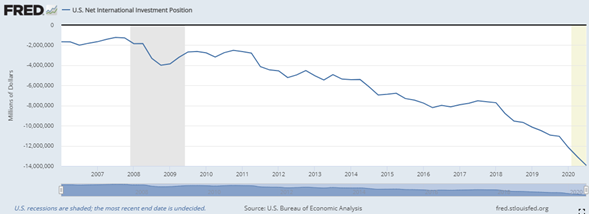

How about US international investment position? The US is the only developed economy which benefits from a considerable deficit equivalent to 66% of its GDP – US$ 14 trillion more international liabilities than international assets, against a US$ 21 trillion GDP -. For how long could the US endure this favorable condition before financial markets push back? No one knows, for it depends, among other things, on the perceived strength of US economy, its institutions, foreign network, entrepreneurship, social cohesiveness and seriousness in its executive, legislative and judicial branches.

But a limit, which ever it is, there exists.

In summary, the US economy is already operating under a positive growth trend that needs support, but on a transparent and credible decreasing basis. The undeterred continuation of monetary and fiscal expansions serves no purpose and could detonate unneeded inflationary pressures and dollar devaluations that benefit no one. At the end of the day, the US is positioning itself, with no need, on a weaker spot.

And prices will certainly reflect that. There is no magic and there has never been one.

Manuel Cruzat Valdés

March 4th, 2021